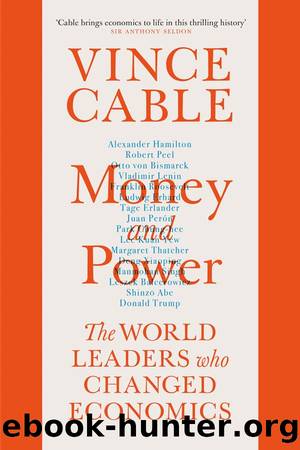

Money and Power by Vince Cable

Author:Vince Cable

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Atlantic Books

British âDeclineâ and the Origins of Thatcherism

Until Margaret Thatcher, the economics of free markets, or neoliberalism, did not have much of a political following in the UK, beyond the political fringes. In the 1950s Enoch Powell was almost a lone voice promoting free markets, privatization, strict monetary policy and cuts in public spending. Indeed, the failure of a Tory government to stick to the last of these led to his ministerial resignation in 1958.6 The Institute of Economic Affairs was established in 1957 as a think tank for free market ideas which were, then, more likely to be absorbed by the much-diminished Liberal Party than the Conservatives. Indeed, the man who was perhaps the most influential economist of that genre â Alan Peacock â was a Liberal, not a Conservative.7

The change in national mood which enabled Margaret Thatcher to introduce policies which were hitherto inconceivable emerged from the collapse of the post-war economic policy consensus in the face of slow growth and economic crisis. The mood was captured in the âdeclinistâ literature of the 1960s and 1970s: from Michael Shanksâs Stagnant Society8 to Andrew Gambleâs Britain in Decline.9 Successive governments had become unable to deliver the post-war, Keynesian, promise of full employment without triggering inflation: a weakness aggravated by trade unionsâ control over labour supply. Mrs Thatcherâs predecessor, Jim Callaghan, expressed the growing sense of pessimism in a speech to the Labour Party Conference in 1976: âI tell you in all candour that that option [of countering unemployment with more public spending] no longer exists and that in so far as it ever did exist, it worked by injecting inflation into the economy⦠Higher inflation, followed by higher unemployment. That is the history of the last twenty years.â10

The second element flowed from the first: inflation spilled over into imbalances in trade (since governments attempted to defend a fixed sterling exchange rate which soon became overvalued in relation to the competitiveness of export and import competing industries). Economic crises followed. The devaluation of 1967 was a harbinger of the 1975 crisis which featured soaring inflation and loss of confidence in sterling, culminating in an appeal for help to the IMF. The IMF medicine may have worked temporarily but it represented a national humiliation; the UK was the only developed country to have needed an emergency loan (an experience shared by Greece after the 2008 global crisis). The austerity measures that followed fed the deepening resentment of public sector workers, which found expression in the 1978 âWinter of Discontentâ and proved fatal not just for the Labour government but for the post-war economic consensus.

Underlying these two factors was a third: the relatively slow growth of productivity (and of incomes, after allowing for inflation). A variety of explanations were on offer: poor quality, unprofessional British management; uncooperative, unionized workers; poor systems of training; inadequate scale; the âwrongâ products being sold to the âwrongâ (ex-colonial) markets; outdated, poor infrastructure; excessive taxes on individuals and companies leading to inadequate savings, risk taking and investment. Some

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Zero to IPO: Over $1 Trillion of Actionable Advice from the World's Most Successful Entrepreneurs by Frederic Kerrest(4570)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4313)

Never by Ken Follett(3957)

Harry Potter and the Goblet Of Fire by J.K. Rowling(3857)

Ogilvy on Advertising by David Ogilvy(3622)

Shadow of Night by Deborah Harkness(3368)

The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman(3079)

Book of Life by Deborah Harkness(2939)

The Tipping Point by Malcolm Gladwell(2922)

Will by Will Smith(2920)

Purple Hibiscus by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie(2855)

0041152001443424520 .pdf by Unknown(2846)

My Brilliant Friend by Elena Ferrante(2831)

How Proust Can Change Your Life by Alain De Botton(2814)

How to Pay Zero Taxes, 2018 by Jeff A. Schnepper(2655)

Hooked: A Dark, Contemporary Romance (Never After Series) by Emily McIntire(2554)

Rationality by Steven Pinker(2365)

Can't Hurt Me: Master Your Mind and Defy the Odds - Clean Edition by David Goggins(2341)

Borders by unknow(2315)